Published

- 10 min read

Russian Blues: A Cat's Tale in Colorspace

A Talkative Cat, a Talkative Language

Note: This essay introduces soon-to-be-published findings, with detailed experimental results and an extended discussion

Russian Blues are famously talkative cats. They chirp, trill, and narrate your life like a tiny sooty sports commentator who is absolutely certain you need continuous updates about the state of the hallway.

This post is about a different kind of Russian blue, but the parallel is hard to resist.

We’ve been working on the geometry of meaning in multilingual language models, and one of the cleanest case studies lives in colorspace, with a particularly interesting example around blue. English looks at the sky, more or less shrugs and says “blue.” Russian does not shrug. Russian will happily subdivide your sky into distinct lexical provinces. In a precise sense I’ll define below, Russian is more talkative in blue.

What we’re actually doing

At a high level, our project asks a straightforward question:

If you learn a big multilingual semantic space from text, can you see cross‑linguistic differences in how concepts are carved up by looking at the geometry of that space?

Our hypothesis proposes that concepts like colors occupy semantic clusters both in our minds and in large language models, with the two being highly correlated. The clusters themselves consist of words that join together with a particular, almost physical, geometry. The geometry influences how we think and how large language models could perform.

Take a modern language model or off‑the‑shelf multilingual word embeddings. Each word becomes a vector in a high‑dimensional space. Words that behave similarly in language end up near each other; words that behave differently spread apart. You don’t tell the model what “similar” means. It discovers a structure that lets it predict words from other words, and the geometry falls out of that learning process. We propose that the semantic space created by the prediction model has a geometry that is correlated with human conceptual geometry as described by cognitive linguistics as proposed by cognitive scientists like George Lakoff (author of Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Human Mind) and Peter Gärdenfors (author of Geometry of Meaning: Semantics Based on Conceptual Spaces)

If language influences thought even a bit, it should leave fingerprints in that geometry. Not in a traditional Whorfian “different worlds” way, but in a very geometric sense: where a language has more lexical distinctions, we should see more structure—more clustering, more curvature, sharper boundaries—in the corresponding region of semantic space.

Color words are a nice testbed because:

- the underlying perceptual space (wavelengths, cones, opponent channels) is shared across humans,

- but languages differ wildly in how many basic terms they use and where they draw boundaries.

So we started with the color region as a kind of sandbox for “geometric Whorfianism.”

The Russian blues

In English, we casually use one basic term for a wide band of the spectrum: blue. We can qualify it (light blue, dark blue, navy, teal, etc.), but the unmarked word is just blue.

Russian lexicalizes a split here. There’s голубой (goluboy), roughly “light blue,” and синий (siniy), roughly “dark blue.” These are not poetical distinctions; they are basic, everyday terms. Russian speakers treat them more like English treats red vs orange than like blue vs navy.

We asked: does that fact show up in the conceptual geometry?

In order to investigate this, we:

- used pretrained (fastText 300 Common Crawl) multilingual embeddings with joint training objectives, so English and Russian color terms are natively aligned in a shared semantic space,

- isolated a region around the color terms (blue, green, yellow, etc. and their Russian counterparts),

- built low‑dimensional subspace projections focused on that region (so we’re not just looking at arbitrary PCA artifacts),

- and then looked at cluster structure and distances.

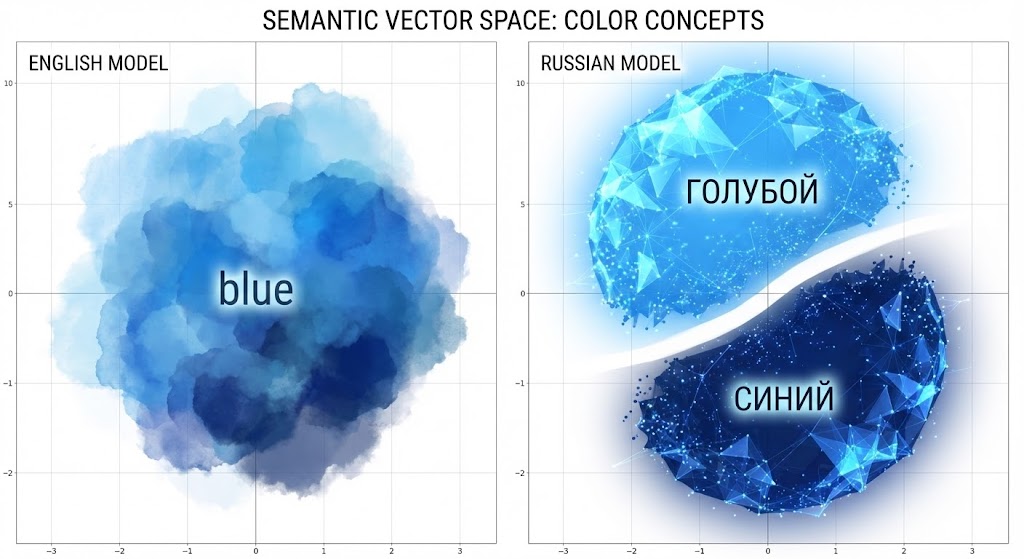

The short version: yes, the Russian blues split cleanly.

In the shared semantic space, the vectors corresponding (directly or via multi‑word phrases) to goluboy and siniy sit in two distinct clusters. The distance between those cluster centroids is large compared to the typical within‑cluster variance for nearby color terms. Roughly: the separation between “light blue” and “dark blue” in Russian is on the order of the separation between distinct basic color categories in English.

If you visualize this subspace, the English “blue” region looks like a single, slightly stretched blob. The Russian blues look like two blobs with a noticeable gap. The model wasn’t told “these are different basic colors.” It inferred that from usage patterns. Russian simply does more with that region. It has more to say.

In the cat metaphor: the English embedding mumbles “blue” once and moves on. The Russian embedding trills a whole sequence of distinct blue‑noises.

Again, that’s a rough analogy. Mechanistically, what’s happening is: the corpus statistics push toward a configuration where the contexts that favor goluboy and siniy are meaningfully different, and the model reflects that difference as distance and cluster structure in vector space.

The experimental Russian blues result: The “Whorfian” validation

Here’s the big methodological point: embedding geometry is suggestive, but it’s not the whole story. If you want to claim a Whorfian effect (even in the “weak” modern sense), you have to show that a language-specific partition isn’t just lexical bookkeeping—it actually shows up in cognition and behavior.

This is why the original “Russian blues” study is so important.

In a seminal paper on the real world effects of cognitive spaces, Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination (Winawer et al. 2007) asked a very clear question: if Russian compels speakers to treat light and dark blues as different basic categories, do Russian speakers show a measurable advantage when they have to discriminate colors across that boundary?

They used a speeded color discrimination task with controlled blue stimuli spanning the goluboy/siniy border. In each trial, participants saw a triad of color squares and had to rapidly choose which bottom square matched the top one. Russian speakers were faster on cross-category trials (one goluboy, one siniy) than on within-category trials (both goluboy or both siniy). English speakers, tested on the exact same stimuli, didn’t show this categorical advantage.

Then comes the clever part: they included a verbal interference condition (silently rehearsing digit strings) and a spatial interference control task. The Russian category advantage was eliminated by the verbal interference task, but not by the spatial one. That’s a strong hint that the effect isn’t just “visual hardware,” but online language involvement during the perceptual decision.

This is textbook psychophysics testing: tightly controlled stimuli + an objective task + implicit behavioral measures like reaction time, designed to connect physical differences in stimuli to measurable differences in perception and decision-making. Put differently: it’s the bridge from “words differ” to “minds behave differently.”

For the geometric Whorfian story, experiments like these are ideal. If we’re going to say that language introduces ridges, gaps, or “metric warps” in conceptual space, we want validation that those warps appear as systematic differences in discrimination, attention, memory, or action—not just differences in what people say.

Languages as manifold sculptors

At this point it’s tempting to turn this into a slogan like “language sculpts reality.” That’s oversold and wrong in the strong form. The physical world, our visual system, and the shared tasks we solve together all constrain the space of viable lexical partitions. It has to be remembered that the strong Whorfian interpretation - that languages lacking a word for something would prevent its speakers from thinking about that concept - is historically disconfirmed.

I think a more accurate picture is:

The world gives us a high‑dimensional continuous field of possibilities. We use concepts to tokenize such inputs into distinct ideas that we can talk about and manipulate using language. Languages apply warping to those ideas, altering their geometry in language‑ and culture‑dependent ways.

That’s still slightly metaphorical, but the mechanics are literal. When a language lexicalizes a distinction:

- it creates stable attractors in usage (“this configuration of context → this word”),

- which show up as dense regions in embedding space,

- and those dense regions bend the geometry around them.

It’s a kind of cultural symmetry‑breaking. The underlying physical stimulus and perceptual manifold is roughly the same across humans. But the particular ways we slice and name it introduce edges, corners, and ridges into the learned representation.

Our experiments suggest that:

- these geometric signatures are robust across different embedding models and preprocessing choices,

- and they line up with known lexical differences (like the Russian blues) without any hand‑engineering.

That’s the part I find satisfying. We’re not annotating corpora with “this is a foundational color term” flags. We’re just letting the model compress co‑occurrence patterns, then reading the compression as geometry.

Why I care

Back to the cat.

I like the cat because I got lucky with a coincidental but applicable metaphor: the breed is literally more vocal than many others. The Russian language is literally more differentiated in blue. Both are, in their own domains, generating more distinct signals along one axis.

This is the kickoff of project umwelt. It takes a long‑running set of arguments—Whorfianism, color terms, cognitive universals—and expresses them in the vocabulary of complex systems:

- High‑dimensional manifolds.

- Cluster structure and curvature.

- Evolved coordinate systems on shared underlying spaces.

- And behavioral validation via psychophysical tasks.

The Russian blues are just a clean example: same visible sky, different lexical tiling, measurable as a different geometry in learned semantic space, and (in humans) measurable as a difference in simple perceptual decisions under the right experimental constraints.

The Geometric Whorfian Hypothesis (GWH) proposes that cognition is grounded in a latent conceptual space shaped by biology and the structure of the world - for example, the color spindle arising from photoreceptor responses and neural encoding - and that individual languages impose systematic, language-specific geometric structures on that shared substrate. A language’s lexicon does not merely label pre-existing concepts but induces a particular semantic manifold: a metric structure with characteristic curvature, boundaries, and anisotropies that determine how regions of the latent space are partitioned, stretched, or compressed. When a language introduces categorical distinctions, those distinctions correspond to detectable geometric deformations in semantic space, altering distances, neighborhood relations, and informational gradients. Under the GWH, linguistic relativity is therefore not a matter of surface associations or verbal habits, but of measurable differences in the geometry through which speakers represent, navigate, and reason about an underlying conceptual world.

The GWH predicts that language pairs in which one has a colorspace topology differentiation that the other lacks, native speakers of the first will possess a similar linguistic category advantage in Russian blues style experiments. We are preparing additional experiments with other languages, including Greek, Vietnamese, Hungarian, and Korean.

Our running process is identifying how we can mathematize and quantify theoretical concepts in cognitive linguistics, and how those findings could inform the design and construction of large language models to take advantage of the linguistic manifolds the way our brains do. These geometries help shape thoughts, and they could be the key to understanding the latent geometry of LLMs and offer a path to training optimization at all levels, alignment modeling, and user interaction dynamics.

For example, instead of approaching multilingualism as an alignment problem, flattening the manifold to an English-centric geometry, could we get higher fidelity and more correct results by preserving the distinct linguistic geometries?

Meanwhile, the cat on the desk is not arguing. She is loudly explaining, again, that the food bowl is 37% less full than it should be.

Different systems, same pattern: some things in the world are just intrinsically a bit more talkative.